‘Places are not made by disciplines. They’re made by people.’

Post-crisis reconstruction expert Marie Aquilino talks conflict and common ground in the backstreets of Paris

10 min read / Rosanna Vitiello

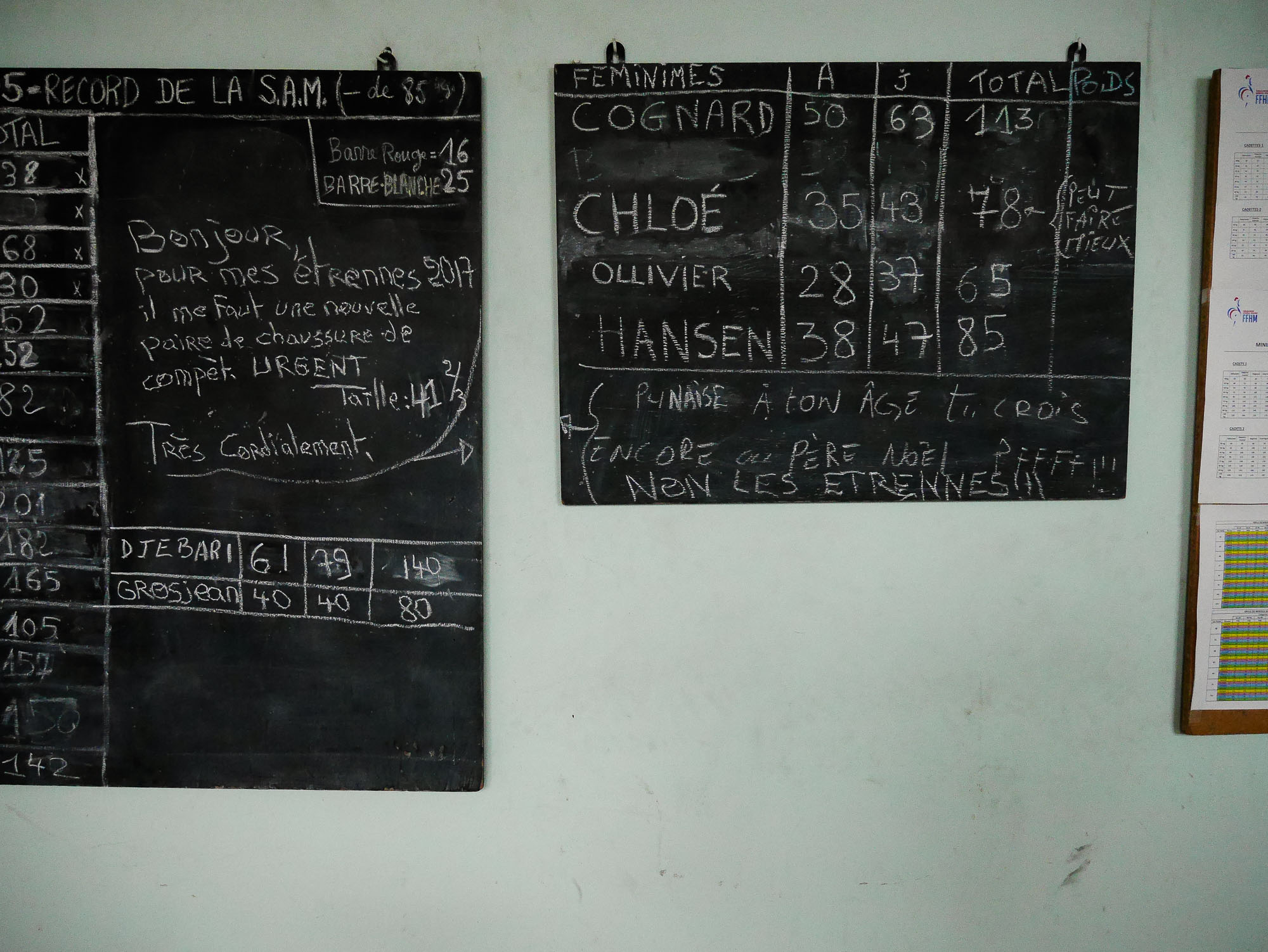

Surprise, optimism and a bold determination characterise our conversations with Marie. “If you’re game,” she says “I’ll meet you on the platform at Barbes Rochechouart. We’ll go from there.” We accept and rendezvous on Paris’s peripherique, where she weaves us through the backstreets bringing us to rest at a small building with a huge history — “the only place that’s truly meaningful to me.” La Société Athlétique Montmartroise — founded in 1898 and one of the most legendary weightlifting clubs in all of Europe.

It’s indicative of the polar worlds Marie inhabits: at once intellectual, human and fiercely real. Her work combines a tenure as professor of architectural history at École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris, with on the ground expertise as a post-disaster reconstruction specialist, and founder of the Haiti Water Atlas Consortium. She’s now drawing on her experiences in a new book, Disaster Junkies: Remarkable Stories of People and Places in Harm’s Way, and applying her learning to Problem Wisdom, a company that teaches visionary impact entrepreneurs and social enterprise leaders to master the craft of problem design. On top of all this she’s a faithful practitioner of ‘halterophilie’, or Olympic style weightlifting. More on that later.

We’re curious to understand her approach to placemaking under such extreme conditions. What really matters? And where do you start? Among the barbells, we hear Marie’s thoughts on the role of narrative in re-building places, what the world can learn from training and why we just can’t wait for another disaster to strike.

Marie, your background is in architectural history – do you think that gives you a different view of the world, of narratives and place?

I’m an historian more than an architectural historian. I'm trained to look for patterns and see the connections and divergences, the ways in which we agree and disagree, as well as the ways in which we are persuaded toward or distanced from one another. I’m trained to listen for the stories.

How did you start working in post-disaster reconstruction?

Completely by accident! I was teaching and wanted to know more about why we're neglecting questions of social justice in architecture.

The Emergency Architects of France were getting going and conferences had just started to pop up. This was just after the Sechzuan earthquake in 2008. I was at a dinner and there just happened to be a young publisher from China sitting next to me, who said, "somebody should write a book on the role of architects in disaster reconstruction and relief." I said, " Well, I'll do it." I didn't have a clue as to where that would lead me.

Did you also see a question of social justice in post-disaster reconstruction?

Yes – it was alarming. Architects are the placemakers, the people who construct the world, but at the time they had very little role in this process.

That's why I built a teaching program we called A World At Risk. In the context of disaster, architects worry that they would just be building rabbit cages or mud huts, not using their design skills, not “making” architecture. In fact the challenges for architects are all the greater in this context. They didn’t know where their place was. It was a question of helping them understand their role.

How do you think that culture and architecture can work together in creating sustainable solutions after a crisis?

Maggie Stephenson, who worked for years for UN Habitat and now is a consultant with the World Bank, has a fantastic ‘Be / Build’ list that answers this question really well.

—

Maggie Stephenson's list asks: do you have the skills to identify what's critical to improving people's quality of life? The skills to build partnerships, to build opportunities to work together, to build models that are replicable, to build speed, and connections between needs and priorities, to build on existing competence by building consensus?

—

And to build the capacity to adapt – that really should be our job. People want to be able to respond to their lives. If you neglect this as an architect or designer, you'll lock them in place and they'll either abandon their homes or they will live poorly within them.

So the ‘Be’ list is: be anonymous, be generous, be helpful, and be strategic. Culture and architecture should be inseparable allies, and these are the principles under which we need to create that alliance.

Bernard, 66, Marie's training partner: 'He practices on the slope to be great on the flat terrain. And so the story of this place, it’s not about convenience. We've turned everything into this story of convenience. You go to other gyms and people are reading the paper, or on their phones and here you'll never see that. Because the tools, this interface with the place is what keeps the thing alive.'

How do crises change places and our relationships with them?

Natural disasters destroy place literally. They ravage and rip apart the way we settle into ourselves. They undermine the ways we carry out the events of our daily lives. They compromise the way we remember.

In most instances, they are a critical opportunity to rebuild in ways that offer more people greater safety and equity. Though safety is given priority, equity is often ignored, unfortunately. They are also a test of what was meaningful in those places in the first place, before the crisis.

What is a crisis? How do you define it?

This is a great question because it’s a conversation that we’re having right now. For the most part, when we're talking about ‘crisis’, we're talking about a tiny percentage of events that take place on a monumental scale, a catastrophic scale, events where tens of thousands of people die, where there’s massive damage to infrastructure and massive cost.

—

What we're not doing is addressing the smaller scale disasters, which are super common. Or those everyday disasters that happen house by house, neighbourhood by neighbourhood. Where – believe me – no one's coming.

—

There's a kind of movement afoot called Everyday Disasters, being led by the invincible John Norton from Development Workshop. He and Ben Wisner are bringing greater attention to the everydayness of disaster. I remember when another colleague was working in Southeast Asia years ago for Emergency Architects Australia. There was no world attention; not enough people had died. But there had been tremendous damage. And the people were spread out over seventy little tiny islands. The EAA team built several models in different places: model homes and a model school. They said, “listen, no one's coming, but here's how you can do this”. “Here’s how you can become more self-sufficient and independent.” It was fabulously successful because people interpreted and used different aspects of the architecture in their own homes, not only to improve their safety and security but also to improve the beauty of them – the beauty of the interior lighting, or the way that the air flows through the spaces.

Why aren't we developing common ways of approaching these events that we can share across the world? Context is very relevant. But there are also ways of developing shared approaches for how to address these circumstances that could help a lot more people.

How do you approach a crisis situation in a particular place?

I'm not an expert in emergency response or management. There is a whole humanitarian aid community for that who are extraordinarily well organised.

I work with longer-term goals: recovery and development. I never decide what problems to tackle, as these are decisions that are made by the community or local actors such as government representatives. It is my responsibility to respond to those decisions, help clarify them, help prioritise them, help explain what the implications are.

You have to really think about the way in which people understand what's available to them as opportunities and choices. For example, working in Haiti for three years, we worked for the Montesinos Foundation with Father Charles. This is a site with almost a hundred children living there, some of them orphaned by the earthquake, others already living on the streets in Port-au-Prince. It has become a residential school.

We assumed that they knew what they wanted. We did all the design work and the planning: lots of different options. We showed them our plans and our drawings, and we debated for weeks at a time.

What we didn't realise, (and what became very evident to me over time) was that Father Charles was already so overwhelmed. He had so much to do and so much to think about. We needed the time to enter into the conversation, help him think through the process so he could better evaluate what we were offering.

One of the priorities that should to be built into any process from the beginning are workshops. Workshops allow for hard conversations, conversations driven by an unpredictable mix of argument and deference. Without them, it’s hard to create opportunities for what I would call abiding one another.

—

Abiding leads to real understanding from which good choices can be made. Giving people choices is not enough because if you don't give them good choices, you haven't given them anything.

—

So what approach are you working towards now?

I'm convinced that we're in urgent need of better, smarter problems. For me, a good problem has the capacity to illuminate the path to common ground.

From what I've seen in terms of missed opportunities, poor decisions and redundant investments, we are not working on the right problems. In the rare instances that we are, we're not working together on them. Then what happens is that the landscape of aid becomes about waste, while common ground remains a rather elusive and almost mystical terrain.

I've started working ‘upstream’. Almost before the beginning, we need to craft and design the problems that we act on with care and with attention. The way in which we shape these problems will determine the outcomes. Trying to back out of what we perceive as a good solution and hit the right problem from reverse is not a particularly good strategy!

How does narrative help your process?

There’s an important idea that my friend Nadia Colburn explored in an essay on Native American traditions of narrative where stories are exchanged back and forth.

—

If we take this approach: ‘you tell me your story, I will tell you mine’, it helps us to listen better. We become invested in the other person's position and priorities by exchanging stories.

—

The investment in one another is enriched as we tell our stories back and forth. Stories that move in both directions allow us to discover the ability to go forward in ways we never would have otherwise imagined.

Does this go beyond working with communities?

It’s certainly a means to overcome not understanding what the other person is saying. This is really common within a group of experts. I refer to it as ‘doing the interdisciplinary’ - thinking that because there are five people in the room and we all do different things, we have an interdisciplinary team.

As an individual, you bring your expertise. And we tend to crave expertise while shunning knowledge. As we do, we hunker down in what we know. The strategy of exchanging stories back and forth can be really helpful in creating new opportunities to think through what ‘interdisciplinary’ means. It provides a shared experience through the exchange of narratives among professionals. Everyone on the team feels somewhat vulnerable within this sort of exchange; but it’s an exchange that also leaves us feeling hopeful and heard.

What do you think is the relationship between the more technical aspects of post-disaster reconstruction and the narrative ones?

Sometimes the technical aspects overwhelm the narrative ones. It’s understandable; however, this is not necessarily something that limits our capacity to use narrative in powerful ways.

If you consider how deeply people value their culture and its artefacts, we very quickly realise the profound importance of narratives of place. In Nepal, for example, the temples are actually living places, not just historical artefacts. There are many rituals and daily activities that take place around them. After the earthquake, many of the temples collapsed into dust and people rallied very quickly not only to protect them but also to save what they could from what remained.

So we can go in and we can figure out why it fell down and how to put it back up. But the narratives of place – not just as narratives of history or myth but of the way in which people organise their lives daily – are very powerful. The way in which we tell stories keeps us living and keeps our ways of life alive.

So after a crisis, how do you go about rebuilding – is it about creating a new narrative for the place?

—

It’s important to understand that making new places is not what people think about first, or second or third for that matter. They want back what they had, what they lost.

—

That’s why it’s hard for people to move forward or imagine what’s possible in the future; they’re not ready to do that. New stories have to come out from the old in a way that makes sense to people. They can’t be imposed from the outside.

Part of the complexity is that people are not ready to move on. At the same time, there is this sense of, "well, if I have to move on, then I’m moving on over here. You’re not going to move me back to the dark ages." You see it happening in rebuilding programs. Communities will think, "if it’s going to be new, then we want modern homes.” They want, for example, a cement block home because that’s what they see in the West. It might not be the safest. It often isn’t. It might not be the most conducive to the climate. But if you start trying to give people bamboo homes, which could be fabulous – spectacular, beautiful, great air and light, that won’t fall down – they’ll think you’re trying to give them a past that they no longer see themselves living in.

There’s a fluidity around narratives during this period. People are looking for stories that make sense.

Marie stands with Nina — the world champion in kettle-bells — 'It's training for life. For military training, for having children, all of these. It's based on the way bodies get used. You can also do power juggling with it! 'In State Academy of Physical Culture in Ukraine we studied history of the Olympic games and I read about this club. So when I came to France I thought 'this was the club I read about and am very fond of!' Why it is interesting? Because Pierre de Coubertin created a modern building, started the modern Olympics. So it is like the culture of the place. It has a story. That's the difference.'

Who do we need to undertake this kind of narrative-driven placemaking?

Everyone. I’m not kidding. Places are not made by disciplines. They’re made by people.

A big concern for everyone involved in responding to disasters is the exclusion of voices - women’s voices, the disabled, the aged.

—

The question about narrative is:

whose narrative is it?

—

We have to be really suspicious of the narratives that come forward, the narratives that dominate, the narratives that win. For example, let’s say we’re having a meeting. We’ve got fifty people in the room and everybody’s shown up to talk about how we want the rebuilding of our community to go forward. There are already people in that room who are used to talking. They are used to imposing the narratives. They’re used to framing the narratives.

What about all of the other people in the room who aren’t so talkative? Or who haven’t had an opportunity to formulate their ideas in that way in the past? How do you help people to get to the point where they're capable of formulating their narrative in this context?

This is why I'm really excited about the idea of exchanging stories, because maybe that's a way to get those other narratives to come forward.

This seems particularly important in that you’re ultimately handing over places to the whole community, not just individuals.

From my point of view, community is place.

—

Places are made and created and designated and set aside and engaged and transformed and lived because people need them to be a certain way.

—

It's our job to understand, respect and interpret these needs in ways that are helpful and resonant. Communities need to be involved from the outset. Communities really should be the people who define the problems, who define what they're willing to invest themselves in, what they're willing to commit to over time.

One thing you have to be really careful of here is not to idealise communities. They're full of diverse and competing interests. A colleague of mine works for Tao Pilipinas, which is a fantastic group of women architects, geographers and engineers in Manila. She said, “Marie, you have to understand just because people are poor doesn't mean they agree."

Is there one principle or piece of advice that you would give for placemaking?

Narrating places is a wonderful way to establish common ground. Telling our stories back and forth: you tell me yours, and I'll tell you mine. That's a powerful means of establishing common ground.

And so Marie takes us to visit a place that might be a kind of common ground of her own: the Société Athlétique Montmartroise in the backstreets of Paris

Why have you chosen this place to bring us?

It’s the last place in the city that you can practice ‘halterophilie’, which is Olympic weightlifting. It’s an ancient sport, a difficult sport and one that very few people are willing to dedicate the time to learn. I started practicing about eight years ago.

Right now there are only 20 of us who are still doing halterophilie here. You can see this is not a gym made for wellness or fitness. Our services are people-sized. This place is invested in by the people who work out here. We’re an association. There is a community of people here. We are Africans, Asians, Americans, French, Italians, Haitians ... People come here because they feel at home. They even bring their kids during school holidays. We look after each other. We talk and tease one another. We talk about one another's cultures and we make fun of each other.

Why do you think it works?

Because of the family aspect of it - we look forward to seeing one another and we greet one another. I mean we literally shake each other’s hands. There is a kind of formality and care for this space that we share. If someone is absent, you notice.

So what does this place mean for you?

Everything. The sport itself ultimately teaches you humility and honesty and patience. It teaches you to be counterintuitive because if you want to go up, you have to go down; if you want to go down, you have to go up. It teaches you enormous patience. The power of perseverance, the power of diversity, we are in a place that really is a mini United Nations.

It clearly has a strong culture. What do you think this place has taught you that you apply in your work?

In haltérophilie if you get the beginning wrong, you get everything wrong. It's a cascade of problems after and it's very difficult to recover.

There are about 24 moves that have to happen before you launch the bar. It's the least dramatic part of the movement, right? You're just lifting the bar off the ground and getting yourself into position. But everything is based on that afterwards: whether you launch the bar high enough with less effort and whether you fall quickly enough. Everything is based on the beginning.

I started to realise that where we go wrong almost all the time in disaster recovery and post-disaster reconstruction is that we don't do the beginning. We start too late. We start largely after the disaster. Now I analyse all the beginning movements and think about analogies with haltérophilie: vantage point and issues of scale.

Compared to the scale of public realm and redevelopment projects, as a place this is a much finer grain.

There's a tendency at times for architects to look at something from up above, but not to be able to zoom in. There's a little apparatus that we call ‘Estavale’ because the last name of the guy who built it was Estavale. It's built exactly to the scale that he needed it to be for it to function well. He built what he needed according to his physical body. It's scaled precisely for that. My thinking about scale is more like Estavale- you need to zoom in and out often to judge the most beneficial scale.

This isn’t a fancy place and yet it’s developed a powerful relationship with the people who use it and actually make it.

The people who come here are sports people. And so all of the fancy stuff that costs money, the TV screens and all the cosmetics, that just doesn't exist here at all. What is here are real tools for people to use. It’s like a carpenter shop. In one, a guy buys all the expensive tools but doesn’t know what to do with them. Then you walk into another shop and the carpenter has five tools, but he can build everything he needs with them.

What you're asking about is the interface between the person and the place, the tools are that interface.