'You need to have a set of conventions in order to rebel against them'

Narratologist Andrea Macrae on narratives that define, defy, and tell us who we are.

8 minute read / Tracey Taylor

It doesn’t take long after meeting Dr Andrea Macrae to realise that what she’s really interested in is communication. A lecturer at Oxford Brookes University, Andrea teaches and researches narrative, stylistics and cognitive poetics. It sounds academic, even arcane - but talk to Andrea and it’s quickly clear that her field is in fact the basic architecture of how stories communicate. Why some stories are powerful and others weak; why some define us and others restrict us; why some are forgotten immediately and others last a lifetime: the answers lie in Andrea’s close analysis of narrative techniques and conventions, and their effects on us.

As well as narratives on the page, Andrea’s work takes her into the wider stories of everyday life through her role as a communications consultant, a specialist in helping charities to hone their messages into something meaningful and effective to raise funds. Taking us on a walk around London’s Brick Lane, she introduces us to another kind of everyday narrative: the ‘living narrative’ of street graffiti, a story in continual evolution.

Andrea, how did you become interested in narratology?

When I was studying for my Masters, I came across literature that really played with narrative. You’d find two different endings to the story in the middle of a book. Then the next chapter would say, "But none of that happened." It's called metafiction: fiction about fiction.

Writers started doing it in the 1700s, when the novel as a form first originated. Tristram Shandy is the first example, but there are a few others, like Don Quixote. Even in really traditional narratives, like Villette by Charlotte Brontë, you get to the ending and the narrator effectively says, "I'm going to let you imagine that there was a happy ending to this story." In a 19th century novel, it was really unusual to ‘disown’ the narrative and hand it over to the reader, saying, "Imagine what you want to imagine."

What was it about those kinds of texts that attracted you?

They got me reflecting on what the conventions of narrative were, because you need to have a set of relatively established conventions to be able to rebel against them.

I was also interested in how these texts play with the destabilisation of the narrative of the self. Subverting archetypal narratives takes the floor out from under you in terms of your own certainty about your narrative of your own history and personal identity.

So how do you define your field - what is narratology?

Narratology is just the study of narrative. It looks at what narrative is, and how it functions in different discourses, different contexts, different cultures, different societies. It can be anything from tiny details of how a title works, to broad topics like how digital narratives in e-literature and digital fiction reflect the plurality of post-modern experience.

Does narratology focus on written texts, or do you think there's a trend towards applying narrative across a much broader range of media?

Narratology as a discipline has conventionally been very literary-based, but there's always been other stuff going on.

“People have always been doing narrative work across different media and discourse types, visual and verbal. Narratives in things like runes inscribed on walls, for example, and graphic narratives in different disciplines.”

People have always been doing narrative work across different media and discourse types, visual and verbal. Narratives in things like runes inscribed on walls, for example, and graphic narratives in different disciplines.

I don't know whether it's called narratology in those disciplines, but I wonder if there's more of a collective mass of people who are aware of what each other are doing.

We quite often encounter the idea that narrative is a universal form of human communication. Do you think there are things that are fundamental to narrative that humans respond to?

I think that, both personally and socially, we have a psychological need to construct narratives.

“Human beings have an innate need to narrativise our history and the events around us in order to make sense of them.”

There's been a lot of work done in psychology on this, and on the nature of trauma - because trauma is in effect an inability to narrativise something, an inability to make sense of something. Socially, we seem to need to construct narratives about our cultural groupings and our national identities to try to understand ourselves.

In doing that narrativising, we are very selective. We choose what to focus on and what to ignore. We can highlight the positive or the negative.

Perhaps it’s a little cynical, but there's also a capitalistic economic function of narratives. There can be a lot of capitalist and political control over national historical narratives. That's partly why the post-modernist crisis happened: because the post-modernists looked at Nazism and the creation of a narrative of the Aryan race that everyone in Germany had seemingly bought into. They thought, "Hang on a minute, we all do this - we've all got dominant narratives of various kinds." For example, there’s a dominant ‘British colonial’ version of British history, and then there's the narrative of the people who were colonised and their version of what happened.

Is this one of the more troubling aspects of narrative — that, in order to make coherence, it can exclude what doesn’t fit?

Yes, exactly. In capitalism, different kinds of political outlets will reinforce certain kinds of narratives about capitalist progress. There's a really interesting parallel in one of our most dominant social narratives in the West: the narrative of the hero, or the ‘super helper’. There will be a crisis, or a problem, or a lack, and one singular force - a hero or a heroine - will come in and save the day. Among other things, it reinforces a capitalist mercantile way of living, whereby you have a lack and therefore you go and buy something in order to solve the problem and reach your resolution and have a happier life.

“As narratives, I think these are quite limiting. They limit the way we behave; they limit the way we see how to live. ”

In the Middle East, narratives are often less linear: they’re long scale epics with lots of different groups involved, lots of different problems, and less of that simple problem-climax-resolution arc. There will be a lot more collaboration as well. It won't just be down to one single saviour force.

How do some kinds of narratives come to dominate others in different cultures?

There's a scale of legitimacy in narratives, where some are legitimised by the people in power at the time. For example, with the King James Bible, King James I (James VI in Scotland) decided that this was going to be our bible - this was the authoritative version. In the same way, different branches of the media will now decide how to narrativise certain events. For a story in which someone gets shot, the headline can be, "Policeman shoots suspect." Or it can be, "Suspect is shot”, completely eliding the role of the policeman. Or "Tragic casualty in shopping mall”, or “Third black man killed in London this week.”

“There’s a scale of legitimacy in narratives, where some are legitimised by the people in power at the time. ”

So what do you see as the more positive aspects of narrative?

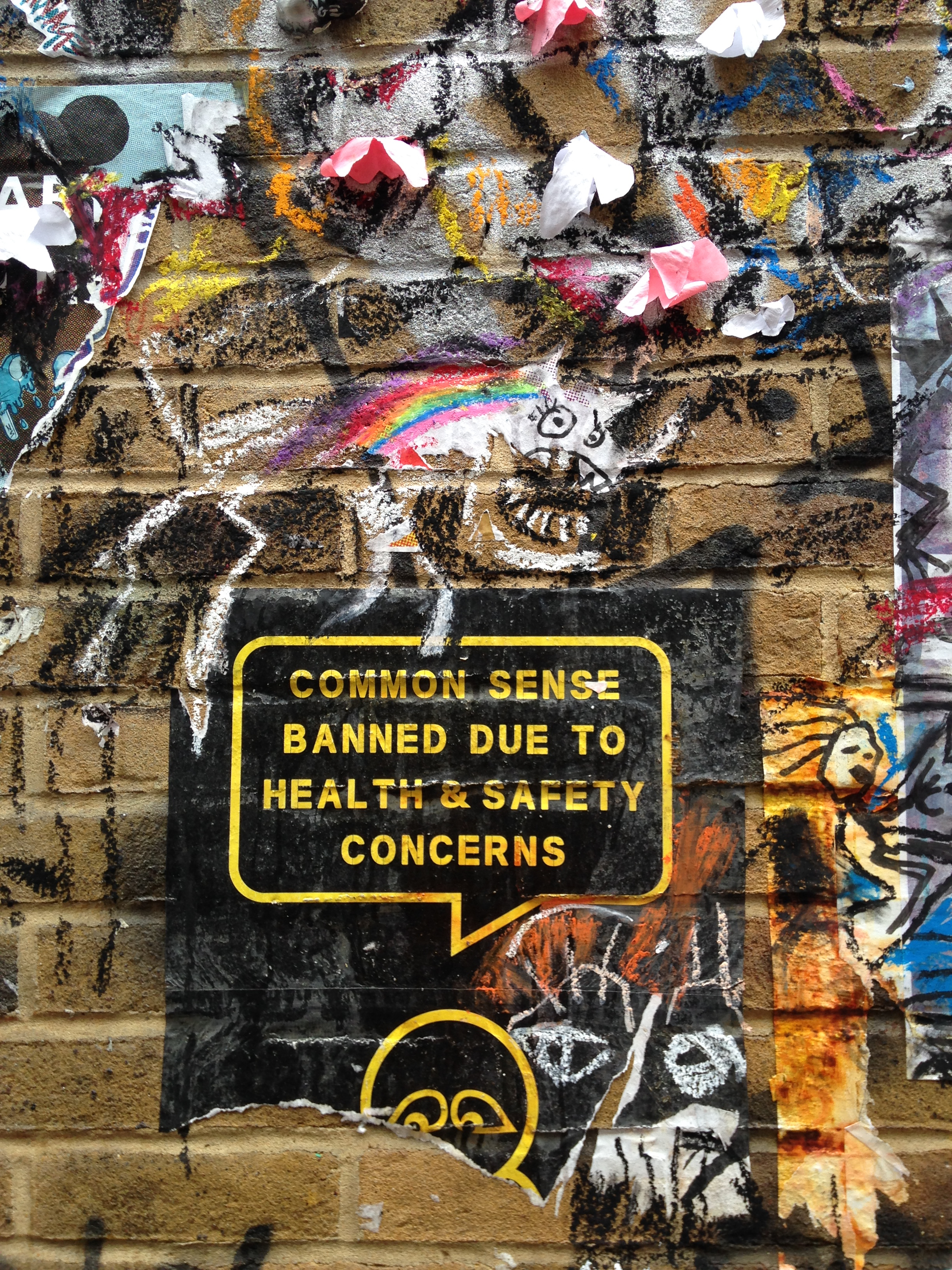

I think narrative in itself is a useful and purposeful thing. One of the reasons I really love graffiti is because it creates a tissue of texts, a living narrative of disenfranchised voices. It's really dynamic. Everyday there will be new tags over old tags. It’s ephemeral; it’s not static in the sense that we tend to like our narratives to be, fixed and solid and firm. It’s also the rebellious expression of views that aren't allowed into mainstream media. That in itself is a beautiful and wonderful thing.

There's an interesting example where an artist called Ben Slow, along with a few other renowned graffiti artists, contributed to a charity campaign for the homeless with murals telling the stories of homeless people. The politics of that are really interesting: the decision that graffiti was the most appropriate way of voicing this particular campaign.

That’s a good segue to your charity work. Tell us how you got involved in that.

Well, I've always been split between academia and something ‘useful’ - put that in quotation marks! Academia is useful in a different way. But because I work really closely with narratives and style and rhetoric, I started looking at the language of charity fundraising and wondering if I can actually help.

For example, I noticed how charity campaigns typically use narratives of representative sufferers. So they'll have a photo of a six-year-old girl and her name - her first name, not her surname, because first names work better - and then a narrative about how she’s suffering. You are the hero figure who can come in and help save her. But there isn't really a resolution. If you give the money, you don’t get the sense that you’ll see it actually happening.

And you work directly with charities now?

Yes, I work with the Commission on the Donor Experience, which has been a two-year project, to help improve the ways in which charities do fundraising. I headed up a project on the language of charity fundraising, looking at examples of dodgy practice and good practice. It’s about saying, ‘This is counterproductive and ineffective, whereas this is brilliant’, and then providing recommendations for how to make sure that you're operating with integrity as well as effectiveness.

So as a narratologist, approaching this work from a narrative perspective, what are the elements you’re looking for in a successful narrative?

It’s not a simple answer, because what's regarded as a successful narrative changes from context to context. And within a text, there will be little pockets of different kinds of narrative strategies interwoven in interesting ways throughout. What I bring to the table is trying to find out what works. Which of those mini-narratives needs a resolution? How explicit does that resolution need to be? It’s about how to construct those narratives in ways which make them effective.

I also bring in research from academia to aid in creating effective narratives. For example, I’m bringing my current work on deixis to the charity sector, as something that they might not otherwise have access to.

What is deixis?

Deixis is a really odd subset of words that we use, where you need the context to understand what they actually mean. If I say a word like ‘chair’ or ‘table’, you’ll have an image in your mind of what a chair or a table looks like. You’ll know what I mean. But if I say a deictic word, like ‘I’ or ‘you’, the meaning changes with the context. When I say the word ‘I’, it means something completely different to when you say the word ‘I’. The meaning changes with every single instance of use. Other examples are spatial and temporal terms, like ‘today’, ‘tomorrow’, ‘yesterday’, ‘here’ or ‘there’.

Why do you see deixis as important to effective narratives?

Those kinds of words are really important in creating immersion in narratives.

“Deictics help to create atmosphere and a sense of immediacy, and to heighten emotional involvement. ”

Deictics help to create atmosphere and a sense of immediacy, and to heighten emotional involvement. You feel like you are there with them. In a way, they force us to project our own ‘deictic centre’ onto somebody else's: we project our point of view into somebody else's point of view in order to understand those words when they are using them.

It's exactly the same with charity fundraising narratives. If they manage the deictics well, the reader will feel more involved. They’ll have more emotional impact.

So in a way it’s an example of a narrative technique that we’re all unconsciously familiar with - even though we might not be able to say what it is or how it works! What do you think are our narrative ‘training grounds’? Where and how do we become fluent in narratives and their techniques?

“We learn about narratives from the kinds of fictions we engage with.”

I don't mean just literary fiction; films and mainstream media also involve strong narrative arcs.

The younger generation now are also conditioned by the narratives of self that are constructed on social media. People curate their own day, their life, their month on Instagram and on Facebook. They're a lot more used to that process of selection and representation. But there’s also a different kind of motivation, which is public facing: “This is the version of myself I want to present to the world.” We all do that professionally more and more too, with our own websites and little bios of who we are.

The tricky thing is if you have a multifarious identity. Sometimes, actually, you've got lots of different stuff going on that doesn't fit into this version of who you are. People get put off if you're not a singular boxable identity. It’s both interesting and problematic.

And the fictional narratives around us must shape or impact on those personal narratives of self as well.

Yes, definitely. I worry in particular about the marriage narrative! Fairy tales and a lot of novels and films end with some kind of union between the woman and her prince or similar. “Reader, I married him”. That’s the resolution. But when you get into your 30s, you start seeing that narratives are lifelong, and there won't necessarily be one climax. Your life doesn't necessarily fit into the approved version of events. Many people still feel shame and failure if they get divorced.

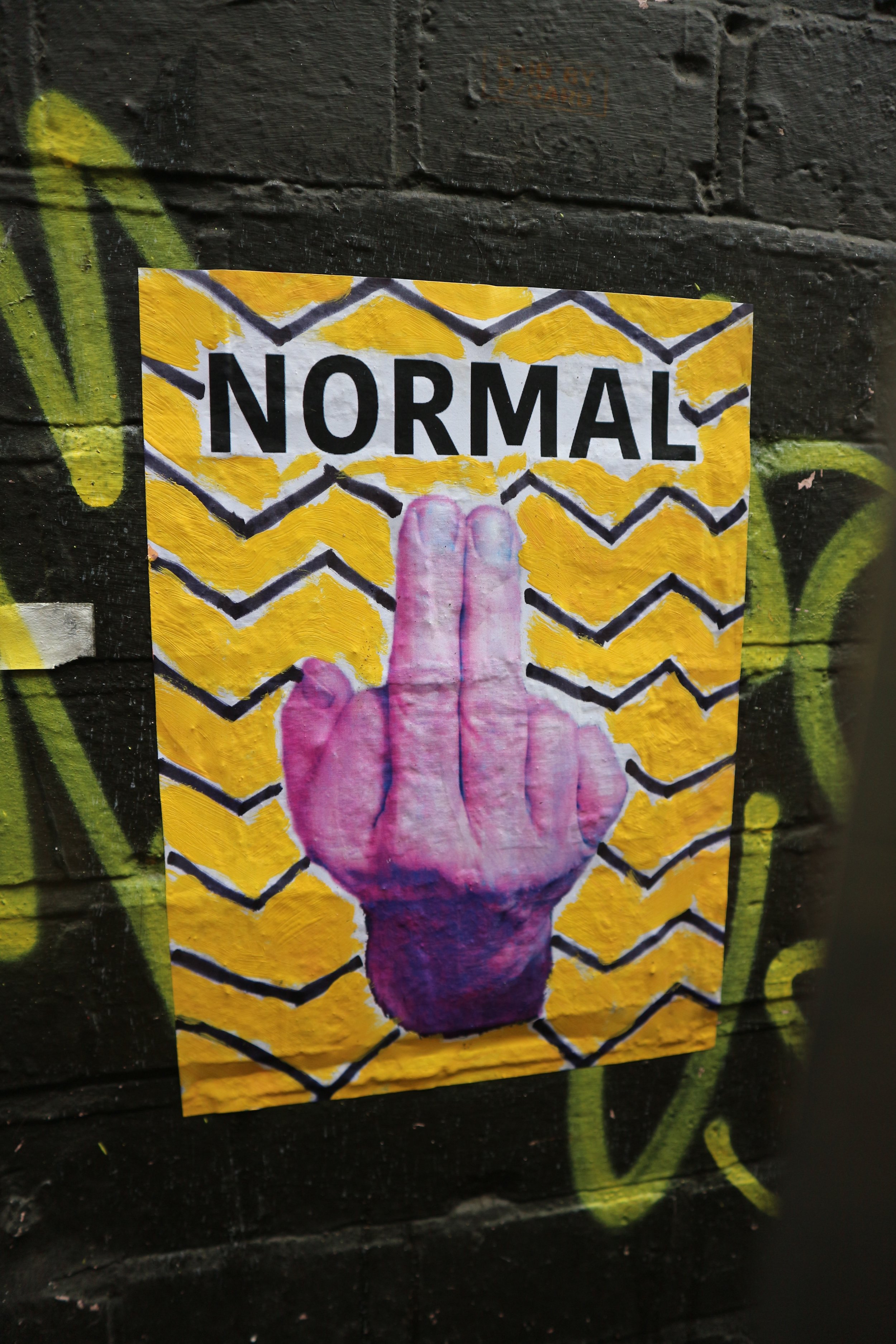

Similarly, if you have a series of beautiful loving relationships, that's not okay. There’s supposed to be just one life partner. Also, if they’re not heteronormative, or if you’re polyamorous, that not okay either. Those people who don't fit into the dominant cultural narratives have to struggle to explain and excuse themselves all the time.

Which is why giving space to counter-dominant narratives is so important.

Yes, really important. I think it's kind of a two way process. Normative narratives dominate us and condition us to the extent that, if we buy into them, life is easier and we are more easily successful. If we don't fit into them, then we are disempowered in lots of different ways. There's a lot in queer culture about the sense of disassociation and social trauma that comes from being apart from the normative narratives.

But, on the other hand, the construction of different collective narratives in things like queer culture can be helpful as well, because you get so much reassurance from finding other narratives that are similar to your own.

“Shared narratives can be reaffirming.”

If you were to give one piece of advice to people - writers, or designers, or placemakers - working with narrative, what would you say?

Respond directly to the piece of narrative that you’re working with. There are many different narratives and different contexts. Be aware of as many narrative tools as you can, and pick the right one for that particular job.

Is there anything else you’d like to add, to finish up?

No. Of course I must refuse to offer closure!

With an appropriate lack of resolution, we follow Andrea on a walk around Brick Lane, where the ever-changing narrative of graffiti slides and spreads across every wall and into every nook and cranny. We start out by a mural just around the corner, on Bacon Street.

Andrea, tell us what we’re looking at.

This is a beautiful mural by Ben Slow. The guy shown here, Charlie Burns, he was a local. He used to just sit in his car on this street. He passed away in 2012. You can also look it up online, where Ben Slow's written about who he was. It's not the kind of thing you would associate with graffiti, but as a memorial, it feels much more human and one to one, like you're having a conversation with Ben about Charlie.

What does this make you think about in terms of the narratives of these street spaces?

It’s about the different rules and permissions that spaces have. The philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the concept of a ‘heterotopia’ to talk about the ways in which the same space can be inclusive to one group of people and excluding to another group of people. It's been used to talk about the ways in which the homeless community exist in spaces.

I think it's a really interesting idea to reveal to us the fact that even spaces which we regard as open and freely accessible are only accessible under certain conditions. I am only free to walk down this street because I have British citizenship, and because I have the money for shoes, and I’m wearing clothes, and I’m not doing anything that will be regarded as illegal in this circumstance. Homeless people are allowed to sit here and there for a while, but they get moved on. I find the concept of the heterotopia helps to flag up that disparity.

Do you think graffiti is becoming more acceptable?

Sometimes it can become a tourist attraction that draws people to certain areas of a city. In Barcelona, when the shutters of the shops are down, they get covered with beautiful work. As long as the work that is on your shutter is not offensive, people don't seem to mind. They actually quite like it.

What I find really interesting is the legitimacy issue. There are organisations and individuals who arrange walls for people to legally use for graffiti. But graffiti traditionally deliberately uses illegal spaces as part of its ‘fuck you’ to the establishment. So when it becomes legitimised and when it becomes an art form - graffiti artists have Instagram, they have art exhibitions of their work, they become published - it creates a really interesting antagonism within the graffiti community about whether that still is graffiti.

LEARNING FROM ANDREA...

BREAKING CONVENTIONS

Narrative is so prevalent among society that we’re often more sophisticated than we think in our understanding of it. And yet that also makes us more prone to falling into the trap of following prevailing narratives without question. “Subverting archetypal narratives takes the floor out from under you in terms of your own certainty about your narrative of your own history and personal identity.” Andrea’s call is to be conscious of the rules — as once you understand them you have licence to break them.

Using the power of narrative wisely

There’s a privilege and a power that comes from shaping a narrative, and it’s one that shouldn’t be taken lightly. Who has the right to tell the story? Who will benefit? And who might be excluded? Used deftly, with a consciousness of the audience, and a narrative has the power to benefit all, but when used illegitimately, then that privilege turns destructive.

In doing that narrativising, we are very selective. We choose what to focus on and what to ignore. We can highlight the positive or the negative.

Picking a perspective

Who will benefit and feel empowered by your narrative? And who will feel disenfranchised? Thinking about point of view and protagonists perspective when creating ‘immersion’ is the secret of successful storytelling. “Normative narratives dominate us and condition us to the extent that, if we buy into them, life is easier and we are more easily successful. If we don't fit into them, then we are disempowered in lots of different ways.”

Allowing for a living story

Despite many people’s desire for resolution, a living narrative can offer a richer story more akin to the experience of the city. Layering elements from graffiti to appropriations as seen among the streets may be messy but allows for the evolution that characterises a place, like the joy of graffiti: "Everyday there will be new tags over old tags. It’s ephemeral; it’s not static in the sense that we tend to like our narratives to be, fixed and solid and firm — the rebellious expression of views that aren't allowed into mainstream media.”

Want more?

Follow Andrea's research at Oxford Brooks University or her personal perspective at

Photography by Manasi Pophale